QakBot (also known as Qbot or Pinkslipbot) is a highly adaptive malware that has evolved over the past decade to evade security defenses. Initially developed as a banking trojan to steal financial data, it has since expanded its capabilities, employing advanced evasion techniques and a modular architecture to facilitate credential theft, lateral movement, and ransomware deployment.

QakBot’s Evolution

The QakBot malware campaign has evolved over the past decade. Since its initial development, QakBot has continuously adapted to major security advancements, implementing significant changes to its design. It has demonstrated the ability to dynamically incorporate new features, ranging from modifications in payload delivery to enhanced persistence mechanisms that evade detection. The following timeline highlights the most impactful changes since its inception.(Zscaler,2024)

2007 – 2016 : Emergence, Expansion and Transition

- QakBot/Qbot emerges as a banking trojan targeting financial institutions

- Developed self-propagation features, such that permitted it to spread like a worm within a network

- Capable to modify Windows registries to establish persistence

- Established an encrypted channel to avoid detection when communicating with a command and control server (C2)

- Developed a modular botnet architecture which allowed the deployment of additional payloads

- Incorporated a feature that detected analysis tools and environments (VMs and Sandboxes)

2019 – 2021 : Access Broker Role, Ransomware Engagement and Evolution

- Focus shifted to providing network access to ransomware groups, becoming an access broker

- Leveraged on macros in Office documents to infect system as phishing email attachments

- Became the primary vector for deploying various ransomware families such as Conti and REvil

- Exploited network protocols and tools to facilitate lateral movement

- Adapted to new infection vectors , using OneNote files and other attachments to bypass email security filters

- Adopted living-off-the-land techniques to execute malicious code stealthily

2022 – Present : Malware-as-a-Service, Law Enforcement and New Developments

- Facilitated large-scale ransomware attacks

- Diversified malware infection methods by employing compromised website and exploit kits

- Maintained a resilient C2 infrastructure by implementing techniques like Domain Generation Algorithms (DGA)

- Operation Duck Hunt lead by the FBI and international partners led to the dismantling of QakBot’s infrastructure, including the deployment of a utility to uninstall QakBot from 700,000 infected systems

- Post-Takedown has encouraged the emergence of new variants with similar functionalities

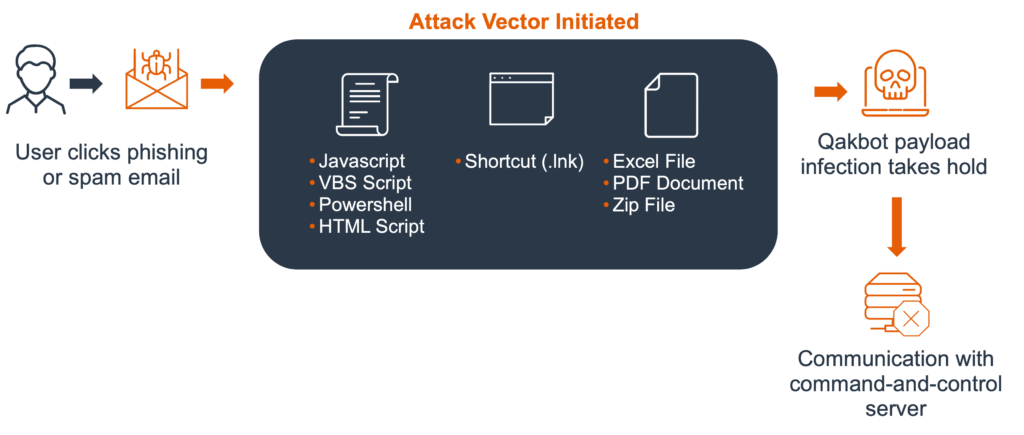

Delivery & Attack Chain

QakBot employs various attack vectors, one of which is distribution through malicious spam (malspam), a method used since its initial development. The subsequent stages of the attack leverage an email distribution technique.

- Malicious email – QakBot uses fake email chains that spoof legitimate email addresses

- Link to zip archive – Email attachment contains a URL link that point to an archive file: “hxxps://prajoon.000webhostapp[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/033/033.zip”

- Downloaded zip archive – The provided URL returns a ZIP file

- Extracted VBS file = The extracted ZIP file contains a Visual Basic Script (VBS) file

- VBS file retrieves malware – The VBS file contains URLs pointing to QakBot Windows executables. Most of these URLs contain a file named **** ”44444.png or 444444.png” “hxxp://centre-de-conduite-roannais[.]com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/last/444444**.png”**

- Initial Qakbot binary – Uses PowerShell,mshta.exe,rundll32.exe, or regsvr32.exe to execute QakBot’s DLL, writing its binaries to disk or executing them directly in memory to evade detection.

- Post infection activity – Maintains persistence by modifying the Windows Registry and proceeds with modular operations, including credential theft, lateral movement, and additional payload delivery (e.g., ransomware).

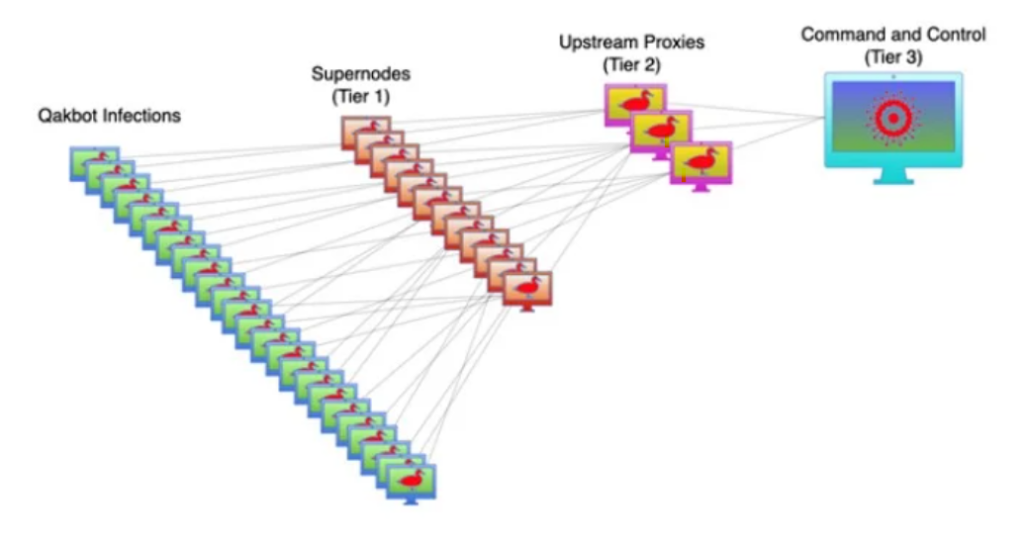

QakBot’s Command-and-Control Structure Before Its 2023 Takedown

QakBot’s dynamic three-tier command-and-control infrastructure was designed for resilient and covert operations worldwide. Prior to its takedown in August 2023, the botnet remained highly active. In Tier 1, select infected computers were promoted to “supernodes” via an additional software module, relaying commands and masking their origin. These supernodes connected to Tier 2 proxy servers that further obscured the link to the main control center. In Tier 3, the main control server issued primary commands, its location hidden by the lower tiers. By leveraging third-party hosting providers and frequently reconfiguring supernodes, QakBot was able to evade detection for years. (CISA, 2023)

As of mid-June 2023, 853 active supernodes had been identified in 63 countries, with frequent changes observed to hinder tracking. However, in August 2023, an international law enforcement operation successfully dismantled QakBot’s infrastructure, severing its ability to issue new commands. Despite this significant disruption, no arrests were made in connection with the takedown. Instead, authorities focused on neutralizing the botnet by redirecting infected systems to a law enforcement-controlled server, preventing further malicious activity. (24by7Security, 2023)

Despite this major takedown, reports indicate that QakBot has resurfaced with new infrastructure. In December 2023, security researchers observed a resurgence of QakBot malware, with updated versions employing new tactics to infect systems. This resurgence underscores the adaptability of such malware operations, even after significant disruptions. (The Register, 2023)

Centripetal’s Perspective

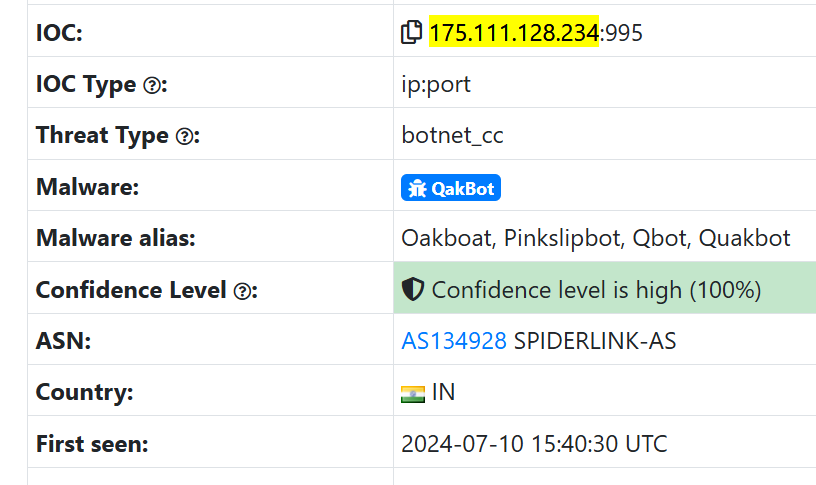

To evaluate CleanINTERNET®’s coverage, we analyzed a sample of the 1,000 most recent IPs reported by Threatfox as part of the Qakbot campaign. Given the high volume of Indicators of Compromise over the past year, this analysis helps measure the effectiveness of our intelligence. The figures below compare Centripetal’s intelligence coverage date with the Threatfox report date.

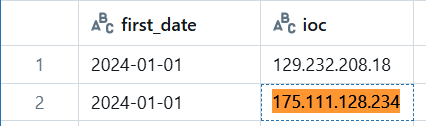

As shown in Figure 3, IP 175.111.128[.]234 was added to the Threatfox report on July 10th, 2024.

Figure 3. Indicators of Compromise sample, sourced from Threatfox

The same IP address (175.111.128[.]234) was present in aggregated deployable threat intelligence as of January 1, 2024. This is seen below in Figure 4.

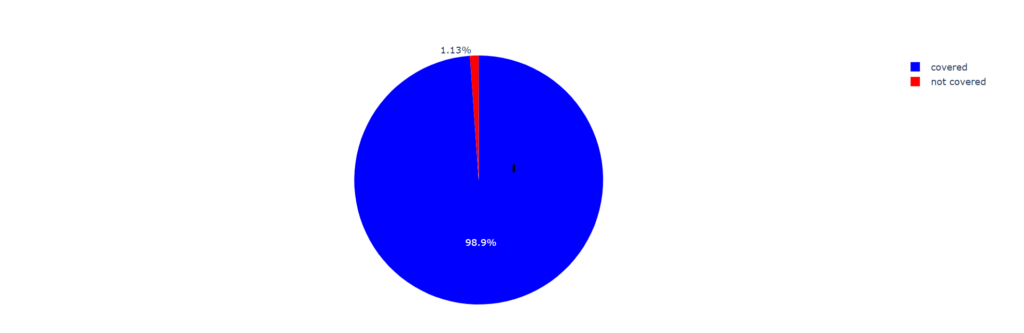

While the first Threatfox sample dates back to February 9th, 2024, Centripetal had already begun tracking these 1,000 IPs as early as January 1, 2024. This highlights the value of proactive threat intelligence—allowing CleanINTERNET to detect and mitigate threats before they are attributed or publicly reported. By leveraging early intelligence, our technology preemptively blocks malicious activity, minimizing the risk of compromise and strengthening cybersecurity defenses (Figure 5).

Over the course of a year, we analyzed 1,000 Qakbot-related IOCs. As of March 11th, 2025, the findings reveal that 98.9% of these indicators were covered by our threat intelligence—meaning they were identified, tracked, or shielded as part of our security solution—while only 1.1% were not covered. This indicates highly comprehensive coverage, ensuring that the vast majority of identified Qakbot-related threats were successfully mitigated. The small percentage of IOCs not covered underscores the importance of continuous intelligence refinement to address emerging or previously unseen indicators.

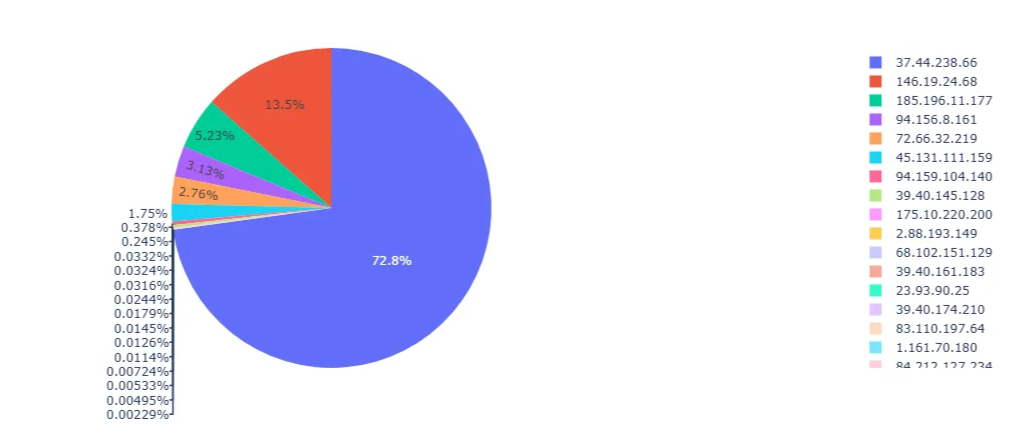

The next phase of our analysis examines the top 20 IP triggers observed across all customers targeted by this campaign. Figure 7 shows that IP 37.44.238[.]66 accounts for 72.8% of these triggers. Our research indicates that multiple threat intelligence sources have flagged this IP as malicious. AbuseIPDB, a well-known database for reporting inbound traffic abuse, has documented continuous reconnaissance activity associated with this IP since 2023. This IP has been observed performing extensive port scanning on both well-known and ephemeral ports across the internet.

o validate the information obtained from intelligence sources, we conducted an additional analysis to determine how much of this attribution was associated with inbound versus outbound activity from this IP across all of our customers over the year-long analysis period. As shown in Figure 8, over 79% of the traffic was attributed to inbound activity, while the remaining 20% was related to outbound traffic.

![Figure 8. Directionality of events from 37.44.238[.]66](https://www.centripetal.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/image-56-1024x498.png)

Another critical insight from this analysis was determining whether the inbound activity resulted in any full connections during its probing attempts. By examining the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) flags, Figure 9 shows that 97% of these connections only reached the initial stage of a full TCP handshake. In most observed port scanning scenarios, the presence of only the Synchronization (SYN) flag confirms that no response was received from the intended target.

This finding suggests that this malicious IP plays a distinct role in the QakBot campaign. Rather than serving malicious payloads or acting as a command and control (C2) server, its primary function appears to be initiating the reconnaissance phase, as defined in the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

![Figure 9. Inbound TCP Flags from IP 37.44.238[.]66](https://www.centripetal.ai/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/image-57.png)

Lastly, attribution analysis by industry reveals that 55.4% of Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) were observed in the education sector (Figure 10). According to cisecirity.org, Qakbot ranks among the top five cybersecurity threats affecting K-12 institutions, accounting for 43% of malware infections in schools.

The disproportionately high percentage of attacks targeting the education sector compared to other industries is a significant concern. CriticalStart.com published an article highlighting the growing interest of threat actors in this sector. Their analysis states:

“The education sector continues to be one of the most targeted industries as cyber threat actors adapt to new security measures and employ more sophisticated targeting practices. In the first six months of 2023, the education industry experienced a 179% increase in attack volume compared to the same period in 2022. Many of these cyberattacks have shifted toward K-12 organizations, whereas previously, threat actors primarily targeted higher education institutions. Often, educational institutions lack robust IT infrastructure and security measures to protect vast amounts of proprietary information related to students, faculty, and staff. As a result, threat actors perceive the education sector as a low-risk, high-reward target, making it an increasingly attractive industry for cyberattacks.”

– CriticalStart

QakBot’s continuous evolution demonstrates its adaptability and persistence as a cyber threat, expanding from financial theft to facilitating ransomware, espionage, and large-scale malware distribution. Despite law enforcement disruptions, its infrastructure and attack methods remain resilient, reinforcing the need for proactive threat intelligence. By staying ahead of emerging tactics, organizations can enhance their defenses and mitigate the risks posed by QakBot and similar evolving threats.

Centripetal is also pleased to offer Penetration Testing and Vulnerability Assessment services to help organizations identify vulnerabilities and reduce risk. If interested, please contact our Professional Services team at profservs@centripetal.ai or reach out to your Centripetal Account Representative.

Resources

- CISA – Identification and Disruption of QakBot Infrastructure

- Threatfox – Historical Indicators of Compromise to date

- Trellix – URLs Linked to QakBot

- Zscaler – Tracking 15 Years of Qakbot Development

- Votiro – The Return of Qakbot: Navigating New Threats in 2024

- Palo Alto Networks – Wireshark Tutorial: Examining Qakbot Infections

- Microsoft – A closer look at QakBot’s latest building blocks (and how to knock them down)

- 24by7Security – International Collaboration Takes Down QakBot Malware Botnet

- Cisecurity – Cybersecurity for Educational Institutions

- CriticalStart – Cybercriminals Attack Vectors within the Education Sector

- MITRE – ATT&CK framework

- AbuseIPDB – Sample IP used for inbound analysis

- The Register – Qakbot’s backbot: FBI-led takedown keeps crims at bay for just 3 months

- Fidelis Security – New Variants of Qakbot Banking Trojan